T1D Guide

T1D Strong News

Personal Stories

Resources

T1D Misdiagnosis

T1D Early Detection

Research/Clinical Trials

Kerry Murphy - Founder of FOLLOWT1Ds Advocates for Schools to Remote Monitor Students with T1D

Kerry Murphy, mother of a child with type 1 diabetes (T1D), advocate, and founder of FOLLOWT1Ds, uses her personal experience to challenge school districts nationwide to FOLLOW parental input, FOLLOW federal law, and to remotely FOLLOW continuous glucose monitor (CGM) alerts for students with T1D.

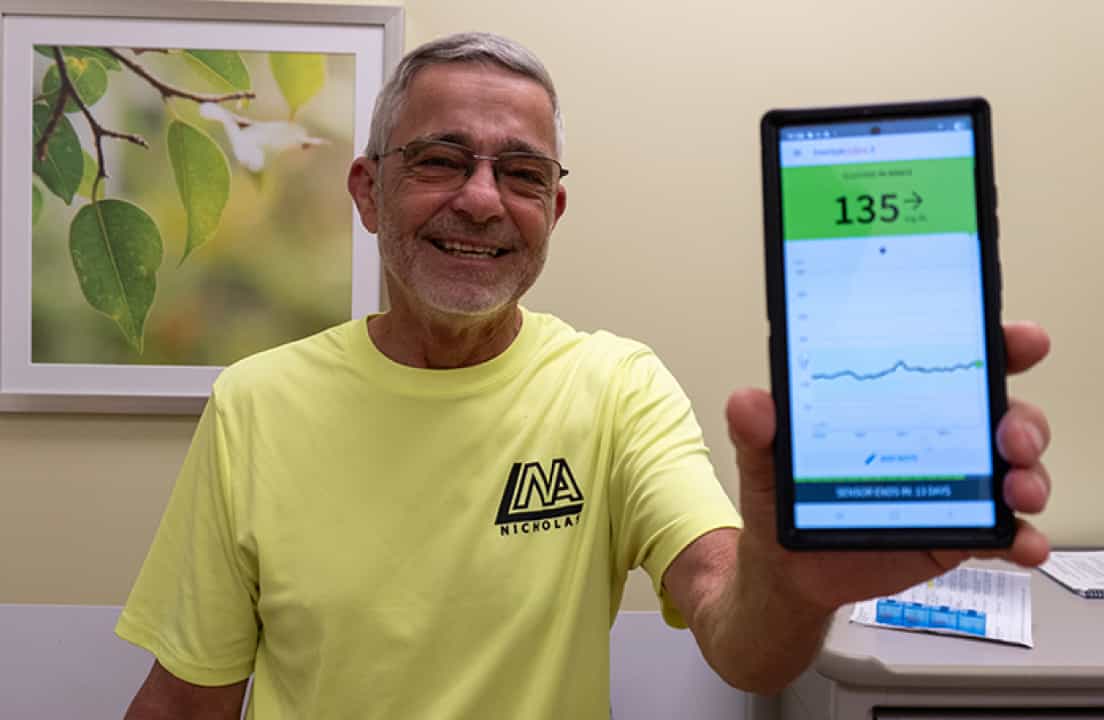

The powerful technology of CGMs and automated insulin delivery systems (AID) has already changed the landscape of diabetes management and continues to evolve. Most importantly, the device wearers can avoid hyperglycemia (blood glucose levels above standard range) and hypoglycemia (below standard range). Both are dangerous and can lead to seizures, coma and even death if left untreated. CGMs also help control overall time in range (TIR), which reduces the possibility of diabetes-related complications.

In the U.S., children spend an average of seven to eight hours a day at school. That is roughly one-third of the day when parents of children with type 1 diabetes must trust their children’s health, safety, and well-being to the school districts.

When technology accelerates faster than our ability to adapt (which is the case with schools' resistance to monitoring CGM alerts on school devices), sometimes parents must step in to force the change. Kerry Murphy is one such parent who cares enough to not only protect her own daughter but also assist other families across the country.

T1DStrong had the pleasure of speaking with Murphy, who has experience advocating for her daughter’s school to remotely monitor alerts from her CGM. She's now leading FOLLOWT1Ds, a group led by parents advocating for nationwide adoption of this accommodation in schools, supported by already existing federal laws and regulations.

Murphy shared her new petition, where she calls on the American Diabetes Association to align their CGM school guidance with settlements commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in 2020. She also spoke about her experience as a Patients Voice Scholarship recipient at DiabetesMine Innovation Days.

About Kerry Murphy

Kerry Murphy received her Bachelor of Science degree in Psychology at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, VA, where she met her husband, Alex. Ten years into their marriage, Alex was diagnosed at 37 with T1D after initially being misdiagnosed as type 2. Alex’s younger sister Erin was diagnosed with T1D at the age of twelve, so he had some idea of what to expect once he was properly diagnosed. T1D diagnoses only continued with other family members, including their niece, Audrey (diagnosed at age two), and their daughter, Violet, diagnosed at age three (she is now nine). The couple’s sons, ages 17 and 20, have tested positive for T1D antibodies; one of them is being followed by TrialNet at the University of VA. TrialNet is a screening that identifies diabetes-related autoantibodies.

In 2018, when Violet was diagnosed, Murphy, now living 45 minutes outside Washington, D.C., focused full-time on her diabetes management. Managing a toddler with diabetes takes extreme vigilance, watching for lows and highs, dosing for food and exercise, all the while accounting for their rapid growth spurts and inability to articulate their feelings—the process can be grueling.

Over the years, Murphy experimented with different methods to manage Violet’s diabetes and ultimately settled on a do-it-yourself automated insulin delivery system called looping. The Loop app runs on an iPhone, receives CGM data every five minutes, predicts future glucose trends using an algorithm, and automatically adjusts basal and bolus insulin delivery to the pump based on the CGM values.

Murphy said that using the Loop app enabled her to keep Violet's A1C between 5.3 and 5.6, the same range they had with injections, all while saving hours a day, eliminating numerous daily physical interactions, administering shots, and making innumerable dosing decisions. Furthermore, it consistently maintained her blood glucose levels within TIR for over 85% of the time, with less than 1% in the low range.

“The appeal (of looping) for me was about maintaining tight target glucose ranges while being able to delegate decisions to Loop, my new assistant. Before looping, we were MDI (multiple daily injections), and she was wearing an i-Port, and I was giving her like 15 shots a day, micro-dosing with a vial and syringe. I was basically a human pump, and I was exhausted.”

For two years during the COVID pandemic, Murphy homeschooled and decided to start Violet on an insulin pump and learn how to build and use Loop. As Murphy put it, “The first week of Covid lockdown, I pulled out my computer and, by the end of the day, had her up and running on Loop. I threw the pump’s PDM (personal diabetes manager) out, and the Loop app I built on her iPhone became her new ‘PDM.’”

Murphy, with help from the Loop Docs, had effectively hacked her daughter and her husband’s insulin pump to send the pump data directly to their iPhones. “So, the Loop app pulls CGM data and the pump data together into one place, and that’s where the algorithm does its work, making predictions about where blood glucose is trending and making dosing decisions to keep the T1D in target range. A couple of months into learning Loop, I was holding my phone and looking at her Nightscout site, which gives me access to all of her pump data and a dashboard to help remotely manage her diabetes. I could see how much insulin she had in her body and where Loop predicted she was going in the next six hours; it was incredibly life-changing for our whole family. Looping can only be unsafe if you don’t know what you’re doing, so building it yourself using the Loop Docs and knowing how to create guardrails is important.”

Last January, Tidepool Loop, a commercially available version of DIY Loop, announced in January 2023 that they were the first automated insulin dosing app to be cleared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Dr. Aaron J. Kowalski, Ph.D., and CEO of JDRF, stated, “This is a major step forward; at JDRF, we have been pushing for interoperability in devices because it will give people with diabetes the option to use the device that’s best for them.”

School and Diabetes

Before COVID, Murphy said she ran into trouble with the school district from day one. “Preschool was great. They did everything I asked them to do; they communicated and responded to her CGM alerts, but I had heard from other parents of T1Ds that public school would be different.”

Murphy contacted the school nurse a year early and could tell right away that the school managed diabetes differently. “I immediately got involved at the district level because I noticed the nurse was passing my tougher questions up the chain of command, and I wanted to communicate with the decision-makers directly. At the start of kindergarten that year, they refused our medical order requiring me to provide all care for two months, initially even refusing to administer glucagon in an emergency. The one thing that saved us during that time was that one week into school, they did finally agree to allow us to provide two devices for them to monitor CGM alerts, audible by the nurse and three trained staff in the office and one for the teacher. These devices kept Violet safe and learning, streamlined communication with staff via text, and saved the nurse a ton of time. I later learned that despite my advocacy, our district continued to refuse it for multiple, if not every, student with T1D that asked.”

COVID hit right as things started to improve with school. Murphy decided to homeschool Violet for first and second grades to avoid navigating even stricter school protocols. After COVID, Murphy sent Violet, now using Loop, back to school for 3rd grade and had her designated by her doctor as independently managing with parental supervision. The two maintained constant communication through text and only looked to the school for responses to audible CGM alerts, emergencies, or when either Violet or her parents requested assistance. Now in 4th grade, Murphy continues to set her alerts to sound before the school’s and intervenes with Violet, and then typically sends a message to the group to ‘disregard’ any impending alerts, allowing all parties to resume learning and working. However, this method of management isn’t possible for all families. Murphy understands that many parents need to rely on the school to be the first responder to CGM alerts and for all diabetes management.

“One of our FOLLOWT1Ds parent advocates, Erin, uses the term in loco parentis – meaning when we give you our child for the school day, you’re now responsible for their physical safety. To force the parent to monitor and be the first responder while they’re at their jobs is ludicrous,” said Murphy. “Many parents are medical first responders themselves, teachers, surgeons, and work in buildings where they can’t have their phones and schools still refuse to remotely monitor the CGM. My sister-in-law’s whole school experience would have been different if people could have seen her numbers and helped her. It could have prevented a lot of emergencies.”

Murphy provided the school with devices to follow Violet’s CGM, but again, this was a secondary backup to her own alerts. “It’s crazy when schools are physically responsible for our children in our absence and do not use this technology when we have it. If they’re not monitoring (CGMs), they may not know the child is in danger until the child drops to the floor in front of the class or goes unconscious or has a seizure.”

Enter FOLLOWT1Ds

In 2020, the Department of Justice mandated that four Connecticut school districts monitor CGM alerts for students with T1D. This demand came under compliance with the federal Americans with Disabilities Act law. Not only must the schools monitor alerts, but they also must provide training on their usage and provide the device.

“I found the four DOJ letters, and my first thought was, ‘These letters say what I’d been saying for five years to people, even the federal government has now said it in writing—it’s the obligation of the schools, and schools are basically violating federal law if they refuse.’ I’m a hard fighter. I thought, this district will finally have to stop trying to take this accommodation away from Violet and I’m going to make them do it for everyone else that asks. I located the attorneys who filed the administrative complaints with the DOJ in Connecticut, Bonnie Roswig from the Center for Children’s Advocacy and Jonathan Chappell of Feldman, Perlstein & Greene, LLC. I wanted their help to do what they did in Connecticut for families in Virginia and beyond. While these rulings were from four Connecticut school districts, if it’s true for one state, it’s true for all states, under the (federal) Americans with Disabilities Act.”

Murphy knew this was a nationwide problem and offered to assist the lawyers from the DOJ cases. She is currently helping them by gathering stories from across the country of schools refusing to follow CGMs. So far, Murphy has found refusals in at least 47 states – where there were one or more accounts of a school's refusal to monitor the CGM remotely. Unfortunately, in many districts, parents are left to try and figure out what to do, many times without access to legal resources to force compliance with the existing federal laws. Murphy hopes to find a way to ensure national compliance and medical safety for students with T1D.

She began gathering stories from parents all over the country and recruiting families to join forces. She founded FOLLOWT1Ds in July 2023, hoping that parent advocates from across the country can advocate together to ensure that all states hold schools accountable and enforce federal laws to protect students with T1D. Recently, Attorneys Roswig and Chappel filed an administrative complaint with the Department of Justice on behalf of families in Virginia, and they hope to have the same outcome as Connecticut in 2020.

“Sometimes the strength of motherhood is greater than natural laws.” – Barbara Kingsolver.

FOLLOWT1Ds Petitions the American Diabetes Association

Murphy has created a petition urging the American Diabetes Association (ADA) to further revise its CGM guidance. “By their refusal to incorporate language from settlement letters commissioned by the DOJ when publishing T1D guidelines, they are contributing to schools' creating blanket policies that are not compliant with federal Americans with Disabilities Act obligations. The Virginia Diabetes Council uses language from the ADA CGM guidance, and they also suggest parents ‘unplug’ during the school day while simultaneously refusing to “plug in” a school device and monitor alerts, so the parents can’t ‘unplug’ at all.” The petition has over 2,250 signatures and is counting.

Murphy says, “We want the nation to see these letters. The ADA Safe at School Program knows about the letters and has previously posted them under the Connecticut laws section of their website only, but they are neglecting to fully support and advocate for implementing them in their own CGM school guidance.”

Their position should be: We at the ADA believe it’s the obligation of the schools to monitor and respond to alerts transmitted by the CGMs of kids with type 1 diabetes and to provide the device and to do the training, or your school might be in violation of federal law.”

All states have an obligation to uphold federal laws, and many trust nationally recognized organizations like the ADA to provide current legal language for their medical forms and school guidelines. “The ADA’s Safe at School Program is seen as this organization that is the end all, be all, of advocacy and education for T1Ds at school, but they are actually contributing to the refusal of what we feel would make our kids safe at school.”

DiabetesMine Innovation Days

Murphy was recently 1 of 10 international T1D advocates chosen to attend the 2023 DiabetesMine Innovation Summit’s Patient Voices Delegation for her notable role in children’s advocacy.

“I was chosen for my advocacy for students with T1D nationwide, my knowledge and use of DIY loop, and because of my experience as a primary caretaker for my daughter’s T1D.” Murphy was most excited to hear from leaders in DIY technology, learn about new CGM technology, and get a sneak peek about what’s on the horizon to improve diabetes management, from insulin-producing cell therapy to trials for cutting-edge genetic testing to distinguish between type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

“I met inspirational and dedicated leaders in the diabetes tech, art, and advocacy world. I also had an opportunity to raise awareness about the struggles of many students with T1D nationwide. When people don’t have young children, they may not be aware of the issues we are having at school; the first step is to make someone turn their head and say, ‘Say what, schools aren’t monitoring CGMs remotely?’ Many people just assumed that it was a common sense request and is being done, and prior to now, parents’ voices have been silenced by school districts, forcing them to fight alone, school by school, district by district, state by state. FOLLOWT1Ds wants to give parents a way to make change together. What my daughter has in Virginia, your T1D should have in every other state under federal law.”

The Power of One Voice

Murphy’s personal experience provoked her to start a movement advocating change in how schools care for T1Ds. Her empathy for other families who shared the same struggles emboldened her to create FOLLOWT1Ds. And while she has united parents in the battle to safeguard students with T1D under federal law, much work remains to be done.

Here’s How You Can Help

If you’re a parent/caregiver of a T1D who struggles with the school district to ensure your child’s rights—sign and share the petition and spread the word about FOLLOWT1Ds.

- Sign and share the Petition.

- Share your story: School Refusal to Follow Form

- Join us on Instagram: FOLLOWT1Ds

- Join us on Facebook: FOLLOWT1Ds

- Share the FOLLOWT1Ds: video

.webp)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)